A deep voice intones a song. A chorus swells hypnotically around it, until, after a moment of silence, the hiss of a flute enters the still air.

Amid the divine flames, the dervish dance begins. The dark ego falls from their shoulders, burns in the heat, dies in the vortex of their steps toward God.

In Konya, in central Anatolia, the dervishes free themselves like moths in the night. An irresistible attraction draws them to whirl, drawn by the call of the divine as a moth is to the light. With their first steps, they drop their black cloaks, stripping themselves of their worldly identity, dying to themselves. In the whirlwind of whirling, they lose awareness of themselves, of their bodies, and of the world around them. The individual self is annihilated in the divine ocean. The moth throws itself into the flame.

Like the insect that dies in the fire, the dervish, through the death of the ego, experiences a spiritual rebirth in a state of pure divine consciousness.

A building burns in the streets of Konya. Despite the firefighters’ intervention, the walls collapse one after another, the bricks crumble, the windows fan the flames of destruction until their last gasp. Then they too fall.

The fire burns in the capital of the whirling dervishes, where in the 13th century the mystic poet Rumi, also known as Mevlana, founded their order. Today, it is the symbolic place of Sufism, home to the most important dervish brotherhood, and the dance remains an important spiritual event.

In Sufism, fire metaphorically represents divine love: a burning and irresistible love, a devouring force that burns away the ego and transforms the human being from a selfish creature into a loving and pure servant of God.

The process is long and painful, but at the same time it leads to an ecstasy called Wajd.

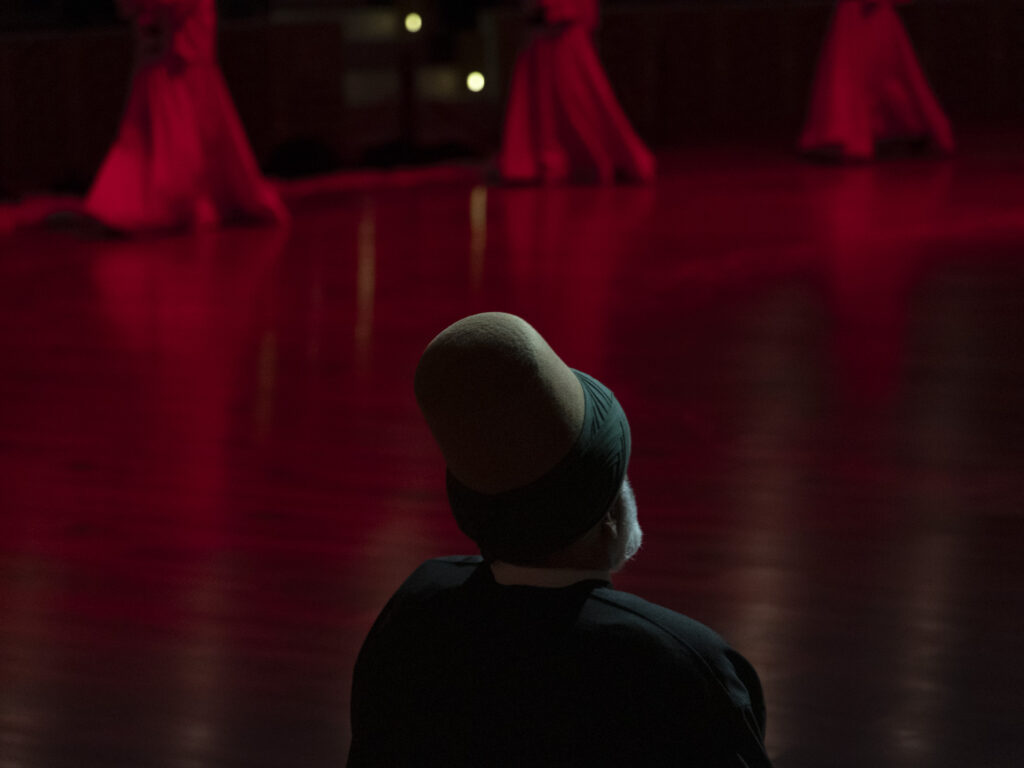

The whirling dance of the Mevlevi dervishes is a physical and cosmic representation of this spiritual fire. The black cloak they wear (Hirka) symbolizes the tomb of the ego and worldly attachments. The white skirt (Tennure) is the shroud of the dead ego. The felt hat (Sikke) is its tombstone. When the dervish begins to whirl, he throws off the cloak, freeing himself of the ego and earthly ties. The movement generates an inner heat, an ecstasy that is the fire of love in action. The dervish himself becomes the fire, a purifying fire that connects earth to heaven. The Master, the Shaykh, observes from a red carpet. He is the fixed point, the divine reference toward which everything converges: the sun around which the planets revolve.

During the Sema, or dance, the songs are joined by the sound of the ney, a reed flute. Its notes are the lament of the soul separated from its divine origin, the breath that fuels the fire of the dance. Thus, from the suffering endured during the fanā, one reaches the Baqā, the state of spiritual rebirth achieved after the ego has been burned away. One is no longer annihilated, but lives in a state of permanent divine consciousness.

The moth, when questioned about love, cannot resist the call of the flame, even if it means its own destruction, because in that destruction it finds its fulfillment and its true life.

A column of whitish smoke rises between the buildings of Konya. Immersed in its fog, Syrian children continue to play in the clearing where they gather every afternoon. The sun’s rays begin to blend with the flames of the building. The city, in its pain, is changing again.