Stones and Molotov cocktails rain down in the heart of industrial Bosnia. The Sodaso building, the epicenter of corruption and a symbol of the crisis, is burning. It’s February 7, 2014. Tuzla, the emblematic industrial city of the country, has been in revolt for two days. It’s the explosion of years of suffering—finally, the long-suppressed rage beneath the ashes of a dark crisis erupts.

The collapse of Yugoslav, and later Bosnian, industry began in the mid-1980s. The decline paralleled that of the Republic and suffered a devastating blow during the three-year war from 1992 to 1995. After the Dayton Agreement in 1995, a wild privatization began: shell companies and powerful oligarchs took over state enterprises. Money, however, started disappearing into a deeply rooted system of corruption.

Between 2000 and 2010, the industrial sector lost about 80% of its workforce. Large companies stopped paying salaries. Workers who reached retirement discovered their contributions had never been paid, leaving them with no savings, no energy to work, and no money to survive their remaining years. Tensions grew. In Tuzla alone, over 10,000 workers labored without pay. The unemployment rate exceeded 50%. On February 5, 2014, more than 5,000 workers from the city’s major companies—Poliolem, Dita, Konjuh—marched toward the center. Initially, they demanded unpaid wages and an end to corrupt privatizations. The response, however, was violent: police charged, and the first arrests were made.

Soon, the unemployed and students joined the workers. On February 6, the city hall was besieged. On the 7th, it was Sodaso’s turn—the privatization agency of Tuzla Canton, a symbol of the betrayal by the post-Yugoslav elite. This marked the peak of the protests. From Tuzla, they spread across the country: from Sarajevo to Zenica, from Mostar to Banja Luka. Bosnia was in revolt.

Today, Bosnia’s industrial situation has seen slight improvement, at least regarding wages. Yet, a silent nightmare lingers, cutting like a scalpel into the lives of Tuzla’s residents. The city’s air pollution rivals that of the world’s worst industrial and mining megacities, often surpassing Beijing or Delhi during winter peaks. In winter, it exceeds WHO guidelines for fine particulate matter by over 10 times (source: IQAir). Soil and water pollution add to the crisis. The root causes stem from industrial collapse. Bankrupt companies abandoned everything overnight—mercury, lead, arsenic, as well as PCBs and dioxins, were left unchecked, free to seep into the environment. Factories still operating haven’t been updated since the 1980s, with outdated, inefficient filters and systems posing extreme health risks.

The thermal power plant, the largest active in Bosnia and the producer of most of its energy, still burns lignite, a low-quality coal. All this happens right next to residential areas. The industrial zone and power plant sit at the city’s edge, their emissions drifting into neighborhoods.

“My daughter has had lung problems since she was three. We have an air filter that makes her life better, but between that and medical care, we spend a quarter of our salary. It’s shocking to see when you buy it—new, it’s blue, but within weeks, it turns black. On my street, in every single house, at least one person has died of cancer.”

Between 35% and 40% of children under 12 suffer from asthma and lung diseases. Cancer rates far exceed the national average, with lung cancer peaking at 38%. Estimates suggest 500 to 700 premature deaths annually due to pollution in a city of around 100,000.

“There are days when the factory smoke and fog turn everything outside white. It’s so thick, it feels like being submerged in a glass of milk.”

- Tuzla has historically been the anti-nationalist city of the former Yugoslavia. A unique place where Serbs (mostly Orthodox), Bosniaks (Muslims), and Croats (Catholics) live without emphasizing ethnic or religious differences. Families celebrate everything: Bajram, Christmas, Orthodox Easter. “We’re a mix of beliefs and cultures, and we don’t care which is which. We celebrate everyone’s holidays.”

- Even when war tried to split Bosnia along ethnic lines, the Dita factory remained a place where Serbs, Bosniaks, and Croats still called each other simply ‘colleagues.’ While clashes raged outside, inside those gates, they still worked together: Serbian chemists monitored tanks next to Muslim workers, Croatian machinists repaired pipelines without asking who was who.

IMAGES

1 – The Thermal Power Plant

2 – Residential Areas

3 – The Sodaso Building

4 – The Thermal Power Plant

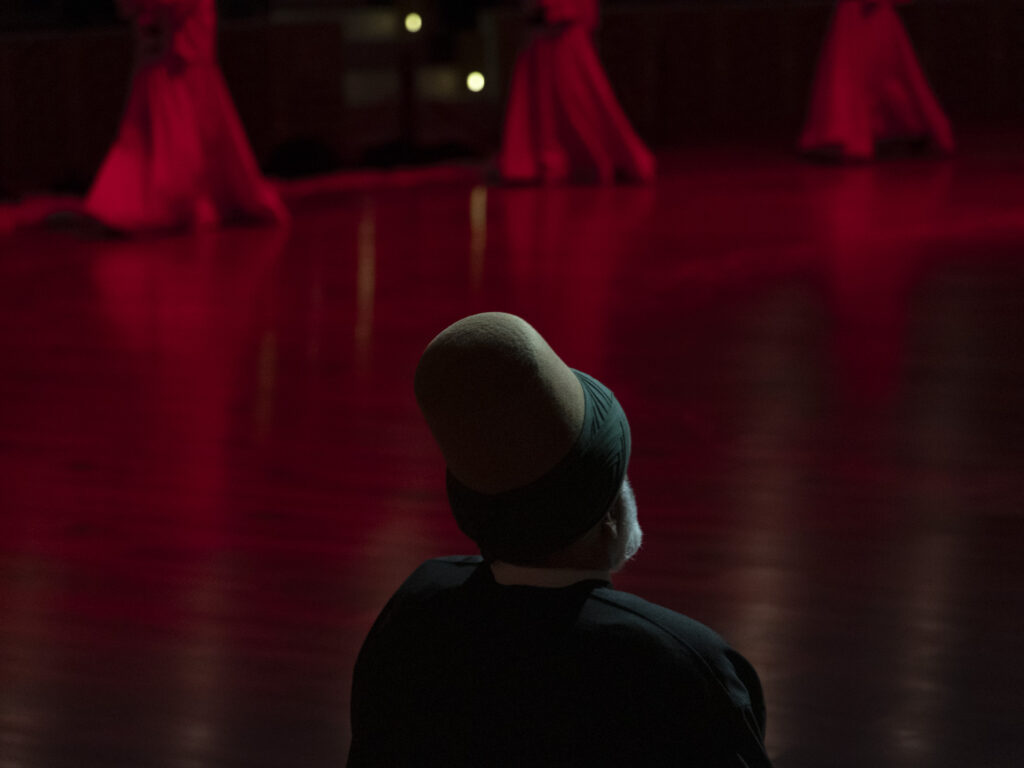

5 – The Atik Behram Bey Mosque, the oldest in the city

6 – The Dita Factory Building

7 – Smoke from the power plant can be seen from dozens of kilometers away

8 – The Tuzla Cemetery

Read it in :

Italiano